The Melbourne hotel wasn’t the dump he had feared. It even boasted a pool, which he had to himself – just how he liked it when doing laps. Especially now there was no Ava Gardner around. He relaxed into an easy freestyle, extending the number of strokes between breaths until he managed a whole length. Not too shabby for a heavy smoker.

Frank Sinatra was always slugging it out, whether with goals or people. Singing was his release, which is why it seemed so effortless – aided by the swimming. Ever the gambler, when he won he aimed higher, and when his star suddenly plummeted below the horizon at the beginning of the 1950s, he still had an eye on the main chance. Sure enough, after some string-pulling, 1953 brought him From Here to Eternity and a Capitol Records contract: the first giving him an Oscar; the second a slew of his finest albums.

Frank Sinatra was always slugging it out, whether with goals or people. Singing was his release, which is why it seemed so effortless – aided by the swimming. Ever the gambler, when he won he aimed higher, and when his star suddenly plummeted below the horizon at the beginning of the 1950s, he still had an eye on the main chance. Sure enough, after some string-pulling, 1953 brought him From Here to Eternity and a Capitol Records contract: the first giving him an Oscar; the second a slew of his finest albums.

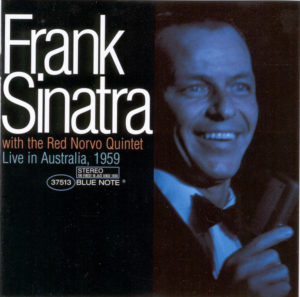

These were riding high in the charts when he toured Australia in ’59, not with a big band for once, but with the Red Norvo Quintet. Melbourne’s two concerts were recorded, and from the second – April Fools’ Day – came Live in Australia, a rare small-band album that was finally remastered and officially released in 1997.

Curiously, many deny Frank was even a jazz singer – some weird snobbishness induced by songs like My Way, I guess. If the godmother of his elastic phrasing was Billie Holiday, his fluidity, switch-backs, drama and mellifluousness were also the marks of a natural storyteller. You get a real taste of this watching him record Moonlight in Vermont in 1965 (https://youtu.be/08D9N4OigC4) and in the must-see Netflix documentary, All or Nothing at All.

Sinatra also instinctively solved a problem that confounded most males. When singing songs of love or heartbreak, they tended towards sobbing affectation, teen-like angst, a feminine falsetto or an emotional vacuum. Frank tapped into an inner truth that exuded a specifically male sexuality, and by 1959 he was the biggest drawcard on earth. He had married and divorced Ava (who, coincidentally or otherwise, was simultaneously in Melbourne filming On the Beach), shot pool with JFK, and turned Las Vegas from a dustbowl into a destination.

More importantly his voice had begun to deepen and darken, and he was constantly playing a game of profound sophistication with rhythm, pitch and timbre; flirting with the words; teasing them and pinching them; sometimes bouncing off the band like a kid off a trampoline.

Forget the fuzzy opening instrumental, and listen to I Get a Kick Out of You, I’ve Got You Under My Skin and his improvising of both words and melody during The Lady is a Tramp. A local horn section joins for three tunes, including On the Road to Mandalay, which Rudyard Kipling’s sister had decreed was a distortion of her brother’s intentions, and vetoed its inclusion on the 1958 album Come Fly with Me (Chicago being added, instead.) With that frustration spurring him on, he carves up what was to become one of his classics. Finally Norvo’s airy vibraphone introduction to Night and Day induces such a free-flowing interaction with Frank as makes for an exceptional version of the song he performed most often.

Although he loved the rocket ride atop a big band, those orchestrations didn’t allow this devil-may-care freedom of dialogue with the other players. Besides, sometimes the string arrangements for Frank’s ballads were laboured, and here you hear him without that weight – although the band sounds like it’s trying to cover for the lack of that usual lushness on Willow Weep for Me, which he probably should have sung just against Bill Miller’s piano, like the gorgeous Angel Eyes.

It’s strange to think that in the 1930s, when “Sinatra” didn’t seem cool, he tried out being “Frankie Trent”. His mother, Dolly, went ballistic: “There is no finer name, none more musical, than Sinatra!” she bawled. Frankie Trent relented. It seems we should all listen to our mothers.

Frank Sinatra with the Red Novo Quintet: Live in Australia, 1959 streams on Google Play and Spotify.