Overnight he plunged from being as bright a star as any in the 1959 jazz firmament to not playing in public. When health issues intertwined with a crippling dissatisfaction with his own art, Sonny Rollins, then the most lauded tenor saxophonist alive, stopped to take stock and absorb the revolution espoused by the free-jazz radicals.

To avoid disturbing his neighbours, he practiced for endless hours on New York’s Williamsburg Bridge. The odd fan saw him and did a double take. Was that Sonny? His return two years later was like the jazz version of the Second Coming. It was the same Sonny who still changed band members like most leaders changed shirts, however, including annexing two of Ornette Coleman’s free-jazz associates (trumpeter Don Cherry and drummer Billy Higgins), as if to get inside the mindset. He gave these new ideas his best shot, and decided they weren’t for him. He didn’t want to jettison chord-based songs, and nor, as one of jazz’s greatest improvisers, did he want a foreground cluttered with instruments other than his own.

Born in New York in 1930 to parents from the Virgin Islands, Sonny had a life-long fascination with calypso. He fell in with the bebop pioneers, playing with Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk and Max Roach, before carving a path of his own. Unlike Miles, John Coltrane or Ornette, he was never closely associated with a particular band. His saxophone was calling-card enough, having a timbre deeper than most tenors, which he used to create long improvisations often based on motifs derived from a song’s melody. With his tightly controlled vibrato he sounded unsentimental – impassive, even – and monumental, like some ancient Egyptian god. Yet a peerless instinct for drama and tension ensured that, rather than being emotionally barren, he was the most primal tenor player before the ’60s made primal tenors the norm. So potent was his playing that he once believed it could change the world.

Sonny had an imposing presence and developed a keen flair for visual presentation. He loved playing unlikely songs (try I’m an Old Cowhand), exemplifying his ready humour – the corollary of his rigour and fierce yet celebratory triumphalism. He never stopped honing his art nor chasing the sound in his head. “I’m always experimenting,” he told me when he was 78. “Looking for breakthroughs.”

In fact, as the key torchbearer for an era when jazz was dominant, he felt obligated to be exceptional. Preparation and performance were worlds apart, however. “When I’m performing, I don’t think.” he said. “A person cannot think and play at the same time, because the music is going by so fast… When I am really playing, I’m not there. I’m standing there, and everything is coming through me… I let the music play me.”

Among a slew of brilliant albums, Sonny released at least one-and-a-half genuine masterpieces. The half-masterpiece was the title track of The Freedom Suite, a three-movement visionary work for his tenor, Oscar Pettiford’s bass and Max Roach’s drums, which, in 1958, was also the first overt pro-civil rights musical statement from an African American. “A lot of people thought it was unpatriotic,” he said. A pause, a chuckle, and then: “Same stuff we have today in the world.”

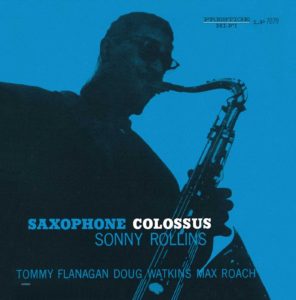

The trio format had already been hinted on the other masterpiece, 1956’s Saxophone Colossus, on which elegant pianist Tommy Flanagan often has a muted presence. Sonny figured most pianists cramped him for room. With Roach and bassist Doug Watkins completing the band, the music’s essence revolved around Sonny’s massive force as a soloist and the proliferation of thrilling tenor/drums dialogues across such pieces as his timeless calypso St Thomas, the cruising Moritat (Mack the Knife) and the ingenious Blue Seven. Add the fact of You Don’t Know What Love Is being much more affecting than any of the ballads on Freedom Suite‘s side two, and this is a record that should be spoken of in the same breath as Kind of Blue.

The trio format had already been hinted on the other masterpiece, 1956’s Saxophone Colossus, on which elegant pianist Tommy Flanagan often has a muted presence. Sonny figured most pianists cramped him for room. With Roach and bassist Doug Watkins completing the band, the music’s essence revolved around Sonny’s massive force as a soloist and the proliferation of thrilling tenor/drums dialogues across such pieces as his timeless calypso St Thomas, the cruising Moritat (Mack the Knife) and the ingenious Blue Seven. Add the fact of You Don’t Know What Love Is being much more affecting than any of the ballads on Freedom Suite‘s side two, and this is a record that should be spoken of in the same breath as Kind of Blue.

Saxophone Colossus streams of Apple Music and Spotify; on disc from Birdland Records.