Old Fitz Theatre, July 13

8/10

Had the good Lord not seen fit to invent Ireland, the post-Shakespeare English-speaking stage would look a nudge threadbare without Goldsmith, Sheridan, Wilde, Shaw, Yeats, Synge, O’Casey, Beckett, Behan and the rest. Despite being London born and bred, Martin McDonagh can just about squeeze into this panoply, thanks to his works’ Irish settings, epitomised by The Cripple of Inishmaan, which is among the great plays of recent decades.

The play’s humour, as black as a bog and as cruel as a child, proves McDonagh an heir to the aching belly laughs and waspish death-rattles of Joyce and especially Beckett. With the wondrous perspective engendered by distance, McDonagh (rather like Barry Humphries in his pomp in relation to Australia) depicts the island of Inishmaan (off the Galway coast) as a nest of grotesques, in which Billy, the title’s disabled teenager (William Rees) is the most normal. Because he has two bent limbs, a penchant for staring at cows and – two towering sins – the gall to think and read (“Did you ever see the Virgin Mary going thinking aloud?” asks Eileen), he is perceived to have a bent mind as well.

Directed by Claudia Barrie (for Mad March Hare), this production maximises the grotesqueness surrounding Billy, while not sacrificing to cheap laughs the essence of humanity, however distorted, at each character’s core. It’s a challenging balance to strike across a cast of nine, and one Barrie has met. That Kate (Megan O’Connell) talks to a stone (for comfort in a worrisome world), for instance, should be as endearing as it is batty. Similarly we must tolerate and giggle at the relentless bullying and spitefulness practised by 18-year-old Helen (Jane Watt), because we know she has found no other means of expressing her fathomless frustration at watching her horizons shrink to spitting distance.

In a strong (if uneven) cast, Jude Gibson triumphs as Mammy, the 90-year-old alcoholic whose antecedents doze on the beds of Dickens and inhabit the dustbins of Beckett. In a play set in 1934, Mammy can see a photograph of Hitler and observe that he must be in two minds about whether or not to have a moustache. Gibson glories in the role, stirring together the character’s mischief, grief and thirst so thoroughly as to make one laugh with a lump in one’s throat.

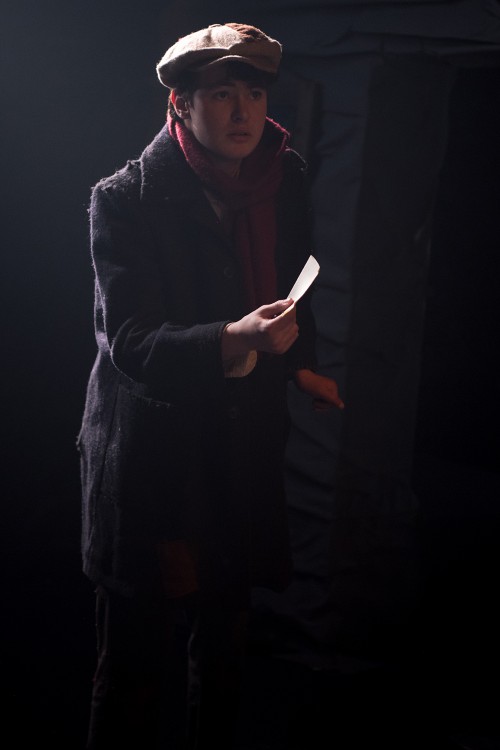

Laurence Coy fills the full-blown role of the island gossip, Johnnypateenmike, squeezing out the alarming blend of juices that constitute him: his gluttony, thieving of secrets, teasing of listeners, and malice toward Mammy all masking a huge, life-affirming heart. Sarah Aubrey claws out a deliciously weird Eileen, whose face might crack if the birds dared sing on a sunny day, and O’Connell plinks an appropriately more fey note beneath the hard exterior of Kate. Jane Watt summons the terror that the gumbooted and boot-gummed Helen holds over all creatures great and small, which they tolerate like bad weather, and Josh Anderson tugs at our sympathy as her put-upon brother Bartley, even if he’s as thick as a plank. John Harding an Alex Bryant Smith flesh out the minor the roles, and William Rees plays the stoic Billy. For sheer veracity Rees is outgunned by some around him, and yet his performance actually works in the context of a production where he’s the still eye of a madcap storm.

Brianna Russell’s design shows appealing ingenuity, and the costumes, sound and lighting sing from the same forlorn hymnbook in a rollicking production of an exceptional play.

Until August 10.