Sonny Sharrock: ASK THE AGES (MOD/Planet), 10/10

Blue Buddha: BLUE BUDDHA (Tzadik) 9.5/10

Darius Jones Quartet: LE BEBE DE BRIGITTE (AUM/Fuse), 8/10

Veryan Weston/Trevor Watts: DIALOGUES FOR ORNETTE! (FMR) 8.5/10

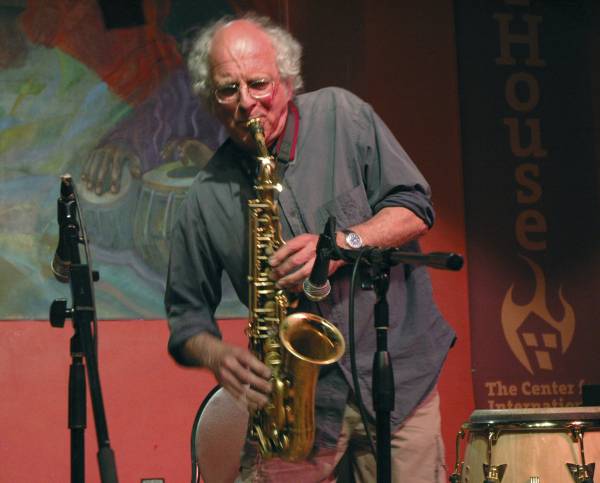

CREDIT: Photograph © 1992 Jack Vartoogian/FrontRowPhotos. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

It was the glass in the face that jazz had to have. The idiom could have rested on the laurels of the 1950s indefinitely, as some current players insist on proving. The ’60s revolution – partly a voice of defiance in the face of racial oppression, partly an outgrowth of wider social upheaval and partly a convergence with the insurrections galvanising other art forms at the time – changed it forever. Alas a weird confluence of conservatism and revisionism would have the ’60s jazz revolution now perceived as an artistic cul de sac, instead of the spaghetti junction of roads leading to countless musical destinations that was the reality.

Alongside another piece of revisionism that ignores the spectacular contributions made by non-US practitioners, this attitude underpinned Ken Burns’ much lauded documentary series, Jazz (2000), on which Wynton Marsalis was a consultant. It is no coincidence that Marsalis-led bands have tended to echo the sounds of the 1950s and before, and have offered little that has opened up the music’s possibilities. The true legacy of the ’60s, meanwhile, has been virtually all that has happened around the jazz world thereafter, whether in terms of freed-up improvisation, cross-cultural projects, or a broadened sonic and emotional palette.

The figures that led the charge included John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, Sun Ra, Eric Dolphy, Don Cherry, Albert Ayler, Charlie Haden and Pharoah Sanders. The output was often furious, dense, agitated and packed with combustible emotion. A blowtorch was applied to the melodic, harmonic, rhythmic, textural and theoretical aspects of its creation, with African and Indian concepts drawn on, and massive experimentation in the relationship between composition and improvisation. Not only does much of the most enthralling jazz of the last half century have its roots in the ’60s, some still seeks to express the spirit as well as the legacy.

The re-release of Sonny Sharrock’s 1992 Ask the Ages is a bridge directly linking the ’60s to now. Sharrock, one of jazz’s more radical guitarists, started out singing in doo-wop groups, and then was frustrated in his desire to be a saxophonist by asthma. His guitar playing first emerged on Pharoah Sanders’ torrential and hugely influential Tauhid (1966), but in the 1970s he virtually dropped out to chauffeur children suffering mental illnesses. He was coaxed back into action by that doyen of New York music, Bill Laswell, and the pair remained close until Sharrock’s death in 1994.

Laswell co-produced this, Sharrock’s last recording before this death, made with the unbeatable combination of mighty saxophonist Pharoah Sanders, bassist Charnett Moffett and drummer Elvin Jones in some of his finest post-Coltrane form. The music is astoundingly vibrant, with Sanders warm and bellicose by turns and Sharrock’s startling originality consistently arresting. In its density, intensity, emotional clout and capacity for sonic surprise his playing fuses Jimi Hendrix with Ayler’s cataclysmic saxophone, and it is as blues-drenched as a back porch on the Mississippi. This is a truly great album, capped by the majestic Many Mansions.

Laswell, who has played bass with and/or produced albums for artists as diverse as Mick Jagger, John Zorn, Brian Eno, John Lydon and Herbie Hancock, is the bassist on a brilliant new opus from the volcanic tenor saxophonist Louie Belogenis, whose band, Blue Buddha, is completed by trumpeter Dave Douglas and drummer Tyshawn Sorey. They create improvisations that vary between sonic avalanches of crushing weight and diaphanous flecks of sound against an ominous silence. Belogenis achieves a roaring intensity combined with a warmth of humanity that also carries echoes of Ayler. It is an expansive sound that can completely fill the sonic image, but he deploys space like a master, and is an acute listener. Who wouldn’t be when you have Douglas’s trumpet slicing through the thickets like a laser, Laswell’s extraordinary idiosyncratic approach to electric bass and Sorey creating labyrinths of rhythmic ideas?

Certainly part of the ’60s revolution’s legacy, this album is also very much a child of the new century.

On his previous releases Darius Jones has proven himself to be one of the key contemporaries breathing something of the 1960s’ fire. For Le bebe de Brigitte, a collaboration with the widely venturing French singer Emilie Lesbros, he reins himself in markedly. But then such interaction between music and text (whether sung, spoken or whispered, and in French or English) also derives from the ’60s, and the dreamlike quality of much of the material carries echoes of some European cinema of the era. For this project Jones’s regular trio is replaced by pianist Matt Mitchell, bassist Sean Conly and brilliant drummer Ches Smith, and even when keeping himself on a leash Jones still deploys a sound and lines to make one’s scalp creep.

Britons Veryan Weston (piano) and Trevor Watts (saxophones) complete the circle of the ’60s legacy. Not only was Watts, like Sanders, Jones and Sharrock, already playing in that era, he were a major part of the proof that jazz could grow and evolve outside the US, being a member of the ground-breaking Spontaneous Music Ensemble. He and Weston further complete the loop by dedicating three improvisations to Ornette Coleman. This is music that seems to have sunlight glinting off its surface, and the interaction between these two players who now share considerable history is amazingly intricate and inventive, whether sprawling, intimate or explosive.