Roslyn Packer Theatre, January 11

8/10

You don’t ask, “Why?” (In fact, one of the cast repeatedly does this for you.) No, you just accept the surreal succession of images that materialise and dematerialise on the stage; accept the music flitting between operatic flights and some crazed dada cousin of jazz, or between elegant chamber airs and thumping rock.

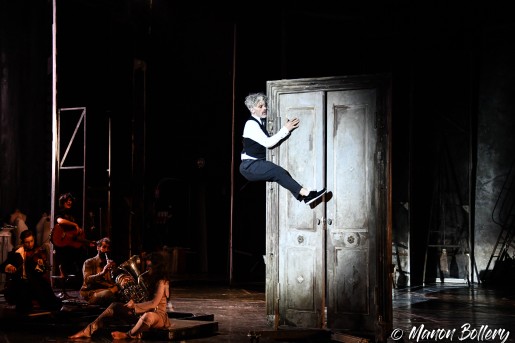

You watch the movement morph from dance to contortion and from clowning to heart-stopping aerial spectacles. You lose yourself in the visual wonder one moment, and are brought crashing back to the reality that you’re sitting in a theatre watching a show that acknowledges it’s a show: one that revels in revealing the behind-the-scene mechanics, and one in which the star can have a mock argument with the front-of-house lighting operator.

That star is James Thierree, who also devised ROOM, directed it, designed it, co-designed the lighting and composed the music – and who happens to be Charlie Chaplin’s grandson. Chaplin, of course, was much more broadly gifted than performing his timeless slapstick in silent films, and that gene has so flourished in Thierree that it’s hard to think of another artist so consummate while wearing such a multiplicity of hats. Beyond the barrage of credits in creating the show, he sings, acts, dances, clowns and zooms in circles above the stage, seemingly with no harness – just holding a rope! He plays several musical instruments, from piano all the way to the Mongolian horsehead fiddle, and many members of his Swiss-based Compagnie du Hanneton are almost comparably versatile.

The magic is initially so intense that you feel long-dormant synapses in the brain suddenly flaring into life, as you connect dots that don’t want to be connected in a show that has no narrative beyond an ephemeral concept of “room” (apparently partly sparked by Covid shutdowns). So tall flats suggesting the walls of a rather dilapidated Georgian mansion continually rearrange themselves. Meanwhile, fragmentary scenes are played out, such as a kissing sequence between Thierree and one of his (named, but not individually identified) collaborators, that, mixing dance, slapstick and acrobatics, manages to be touching, evocative and funny simultaneously.

At one point the ensemble members move like so many wind-up toys, and at another Thierree is some mad version of Frederico Fellini, directing, conducting and choreographing his performers as if making a zany, dream-like movie. His mime skills are phenomenal (including feigning that a violin case weighs a tonne), and his singing is vaguely reminiscent of Lou Reed, only with more accurate pitch and a wider range. If he had suddenly launched into Reed’s masterwork, Perfect Day, it would not have been out of place amid his own material.

The fourth wall is routinely exploded in many ways, including Thierree giving voice to our own thoughts. “What’s this sequence? What does it mean?” he asks at one point. “It’s stupid. What’s the theme?” And later, “I understand. We all want an explanation. You want to be able to go home and say it’s all about…”

But you can’t. What you can say is that for all his surging imagination and brilliance as a performer, Thierree lets weaker sections creep in among the exceptional ones, and the 100-minute show would be stronger still for being shorter. Nonetheless, in an age when “surreal” has been debased to become a synonym for weird or bizarre, Thierree keeps one of the last century’s great artistic movements alive by making theatre that is truly oneiric.