She wasn’t even a jazz singer. She was a guitar-strumming folk singer who fled Maine for the big time in New York. The big time gave her a contract, one album, and then spat her out, but she kept plugging away, falling into a relationship with the Paul Motian Trio’s brilliant bassist, Larry Grenadier. Motian, a pivotal drummer/composer as well as band-leader, asked Rebecca Martin to sing on his new album. Despite the giant leap out of her comfort zone, she accepted.

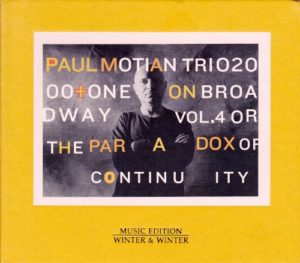

The result was 2006’s On Broadway Vol. 4, subtitled The Paradox of Continuity. Completed by tenor saxophonist Chris Potter, Motian’s trio had Martin and pianist Masabumi Kikuchi guesting on different tracks. Together they tore away all the Broadway material’s frilly edges, exposing essences conveying a misty, romantic nostalgia, like an old love affair remembered with fondness rather than bitterness.

The opening instrumental, The Last Dance, conjures the lyric: a venue closing in the wee hours; two people dancing on toward dawn, for fear of separation. Potter’s tenor emits lonely, gull-like cries, the piano makes wry asides, and the bass occasional massive, supporting columns of sound, while Motian’s brushes scratch and scrabble like the dancers’ feet.

Martin joins for Tea for Two, and it’s as if someone stole a distant childhood memory and held it up to a distorting mirror. The song always seemed as disposable as a wet tissue, but now, sung in slow motion, it suddenly aches with a new poignancy. Martin sings it tentatively, vulnerably; injecting a quiet desperation, so the question, “Can’t you see how happy we would be?” carries unexpected irony, and Potter’s tenor, fluttering and crooning about her, becomes the lover to whom the song is addressed.

“The experience of making music with Paul changed my life, and set me on a completely new path in how I approached my own music,” Martin said. “It was the first time I’d recorded without a chordal instrument, and that was a revelation for me. It was also liberating to be working with one of my idols in an atmosphere that was completely down to earth and blue-collar.”

Motian had shot to prominence in 1959 with the hugely influential Bill Evans Trio, and went on to play with Keith Jarrett, among others, until primarily focusing on his own projects. In these he showed that the best way to keep jazz truthful, meaningful and fresh was to strip off its accumulated trappings of technique. In his last 20 years he was the near-perfect improviser, letting his ears dictate what to play, with no interference from practice, intellect or muscle memory – a greater challenge than boundless dexterity. Liberating jazz from the quicksand into which it was sinking, he demonstrated how to enter the surrounding music and simply be, rather than consciously playing an instrument.

His drumming let time float in some elevated zone beyond the concrete pull of gravity. Rather than defining rhythm in hard lines, Motian blurred and smudged it on to the musical canvas as an evocation of – or counterpoint to – the music’s emotional content. In Martin he had a singer who compounded those emotions with world-weariness (“I’ve mortgaged all my castles in the air”, she sings in Everything Happens to Me) rather than self-pity, and without self-consciousness.

His drumming let time float in some elevated zone beyond the concrete pull of gravity. Rather than defining rhythm in hard lines, Motian blurred and smudged it on to the musical canvas as an evocation of – or counterpoint to – the music’s emotional content. In Martin he had a singer who compounded those emotions with world-weariness (“I’ve mortgaged all my castles in the air”, she sings in Everything Happens to Me) rather than self-pity, and without self-consciousness.

The instrumental Never Let Me Go is just as potent, Kickuchi showing how his delirious aural dreams fitted perfectly with Motian’s genius for opening up options. Throughout the album you hear the group interaction become more telling the less everyone plays; a frugality that distils the purest musical poetry. Indeed Motian’s greatest art flowed in his 70s – just when many are settling for the safety of reproducing what they know will work. By example he also elicited his collaborators’ finest work, his own rigour being a mirror that forced them to confront the “to play, or not to play” conundrum. He died in 2011, aged 80. Potter, Grenadier, Kikuchi and, above all, Martin would never sound better than they had with him.

On Broadway Vol. 4: Spotify and Apple Music; on disc from Birdland Records.