He was 75 when he finally did it. That’s an age at which most singers’ breath-control is declining, their range diminishing and their tone becoming clouded with rasps and wheezes. No one told Tony Bennett. He walked into a New York studio in 2001, four weeks after 9/11, and delivered the definitive jazz vocal of his career.

Perhaps it was because he was a guest, just there to sing one track, rather than having to sustain his voice for repeated takes of a dozen songs. He could breeze in and breeze out; maybe knock it off in one take.

Singing had always come easily to Antony Dominick Benedetto, born in 1926. When only 10 he sang at the opening of New York’s massive Triborough Bridge project, paid with a pat on the head from the mayor. In his teens he was a singing waiter, before briefly attending the School of Industrial Art, where, as well as studying painting (his other passion), he began to acquire the vocal technique that would allow him to have such an astonishingly long career as to record versions of Gershwin’s Fascinatin’ Rhythm 69 years apart.

Of course it wasn’t all spaghetti and meatballs. The Great Depression was brutal, he lost his father in 1936, and during WWII he had what he called a “front-row seat in hell”, seeing action in the Battle of the Bulge, France and Germany. Despite this the army demoted him for daring to eat with a black friend from his high school days.

After the war he studied bel canto singing at the American Theatre Wing School, improving his impeccable technique yet more. In 1949 Bob Hope heard him, took him under his wing, and turned the guy who was working as Joe Bari into Tony Bennett. A contract with Columbia Records followed, and Bennett swiftly became a hit-making machine. But the songs were usually over-produced, and when he did make jazzier records they sounded stilted compared with Sinatra’s, even though Frank declared Bennett his favourite singer.

He weathered the Beatles, marched side-by-side with Dr Martin Luther King and refused to perform in apartheid-torn South Africa. Then his career imploded. Columbia forced him to sing pop, the results were embarrassing, and he was dropped. Starting his own label, he recorded two duet albums with supreme jazz pianist Bill Evans, but his exceptional singing was still closer to cabaret than jazz, and the sales were modest.

A disillusioned Bennett turned to substance abuse, nearly killing himself before his son Danny became his manager, and astutely turned his career around with TV appearances ranging from David Letterman to The Simpsons. 1994’s MTV Unplugged: Tony Bennett – “I’ve been unplugged my whole career,” he quipped – sold him to a new generation, as did subsequent collaborations with kd lang and Lady Gaga.

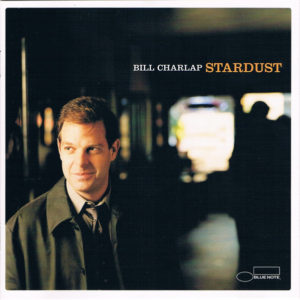

So when he walked into that studio in 2001, he’d known the highest highs and the lowest lows, and knew his voice’s age-imposed limitations. The album, led brilliant pianist Bill Charlap, with bassist Peter Washington and drummer Kenny Washington, was a collection of Hoagy Carmichael tunes called Stardust, the other gold-plated guests being singer Shirley Horn, guitarist Jim Hall and saxophonist Frank Wess.

So when he walked into that studio in 2001, he’d known the highest highs and the lowest lows, and knew his voice’s age-imposed limitations. The album, led brilliant pianist Bill Charlap, with bassist Peter Washington and drummer Kenny Washington, was a collection of Hoagy Carmichael tunes called Stardust, the other gold-plated guests being singer Shirley Horn, guitarist Jim Hall and saxophonist Frank Wess.

Without Bennett it would already be among the great jazz albums, but his reading of I Get Along Without You Very Well is on another level. He begins a cappella, before Charlap and the whispering rhythm section join over the slow, slow tempo, with Bennett finely balancing, syllable by syllable, unendurable sadness and a facade of stoicism. Certain words flare up in a way that lances your central nervous system, while others are delivered with a wry, what-could-have-been smile. That his voice is oxidised like aged copper makes the emotional impact all the more telling and truthful, and Charlap responds with a pithy solo of exquisite touch.

Bennett was not just the master of the Great American Songbook, he actually coined the term, and, after a life of loving jazz, he finally minted a masterpiece of the idiom.

Stardust streams on Apple Music and Spotify.