John Coltrane: Offering (Verve)

Trevor Watts: Veracity (FMR)

Cedar Walton: Reliving the Moment (HighNote/Planet)

Various Artists: Black Fire! New Spirits! (Soul Jazz)

He changed the lives of listeners, and he changed the course of jazz. John Coltrane inspired people to take up the saxophone or rethink the way they played it. His profound spirituality made some among his millions of admirers investigate that dimension, while others tried to emulate the torrential energy of his performances. They may as well have tried to imitate a tempest. Witnesses of his 1960s concerts speak in awe of experiencing something between shell-shock and religious revelation. The impact is there on his albums, too: music to match the power of Picasso’s Guernica, but with a warmth of spirit the painter could never equal.

Few albums, therefore, can arouse such curiosity as the unearthing of a never-released live recording of the most potent musician that jazz has produced. It documents a Coltrane concert from 1966 (nine months before his death) that became almost mythological because not only did he blaze away on his saxophones, he actually sang!

So is it the Holy Grail of lost Coltrane recordings? Almost. The man himself is in towering form, but the single-microphone recording is fundamentally flawed, despite painstaking remastering. Nonetheless it will rekindle some old debates about jazz’s greatest improviser, and the radical course his music-making took in his last 18 months.

Coltrane’s stature required no posthumous magnification. He had recorded acknowledged masterpieces such as Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue and his own A Love Supreme, and had led the most significant, influential and powerful band of the 1960s. He revolutionised the playing of the saxophone, and layered into jazz not only a spiritual element, but also concepts borrowed from Indian classical music.

When, however, he disbanded his early-’60s “classic quartet” and formed a new band to free up his approach even further, he polarised listeners. Apparently Coltrane himself thought his music was now reaching beyond jazz – beyond any idiom – towards the purer form of expression that may be heard on Offering. His own playing has a blowtorch intensity and his sound, especially on tenor, is as majestic as any instrument ever.

With him are his wife Alice (piano), Sonny Johnson (bass, deputising for Jimmy Garrison), Rashied Ali (drums) and Pharoah Sanders (tenor), plus guest alto players and percussionists. The material includes Leo, on which, following an Ali solo, Coltrane sings a wordless improvisation of absolutely primal force, while beating his chest to create a tremolo effect. His ensuing tenor solo is based on his vocalised motif. He is also moved to sing briefly during a tumultuous My Favourite Things.

This must be heard, with two provisos. One is that some of Sanders’ screeching will frighten domestic animals (and possibly humans, too!), and the other is the recording quality, with the saxophones dominating the aural image, although the piano, bass and drums are amply audible when they feature. So in purely sonic terms, no, it’s not the Holy Grail, but it is an extraordinary double album, brimming with the profundities of a man who continues tower over the art of improvisation, across the idioms and probably the centuries.

Examples of his legacy abound. The late Michael Brecker, a significant saxophone virtuoso in his own right, was a high school Coltrane devotee who first heard his idol at this very concert, and immediately changed from alto to tenor. Bob Berg was another saxophonist hugely influenced by Coltrane. A newly released live album by the pianist Cedar Walton from 37 years ago has Berg in particularly burning form in a band including trumpeter Freddie Hubbard and drummer Billy Higgins. They storm across a version of Coltrane’s Impressions, although sometimes Berg’s admiration for his hero is a little too blatant.

The double album Black Fire! New Spirits! is a companion to the book of that name mentioned in these pages in September. Alas this is not nearly as strong a compilation as one might have expected, given the quality of the book’s essentially photographic documentation of 1960s African-American jazz. The saving graces include tracks by Yusef Lateef, Don Cherry, Archie Shepp and Joe Henderson. Shepp, who contributes the album’s most dramatic piece and who makes one of the brawniest sounds ever heard on a tenor saxophone, also took up the instrument after hearing Coltrane, and he collaborated with the master on the great Ascension album. Although Henderson’s tenor playing displays little overt Coltrane influence he did choose to use pianist McCoy Tyner and drummer Elvin Jones from Coltrane’s “classic quartet” on the albums that established him in the 1960s, and he would later collaborate with Alice Coltrane.

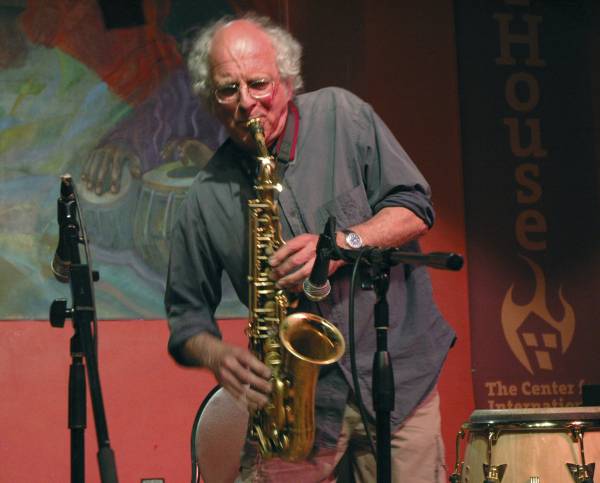

Who knows where Coltrane’s art would have gone had he not died at 40, but it is likely he would have continued to push the boundaries of the saxophone and of jazz. Two players who have been prominent in continuing that work have been the British saxophonists Evan Parker and Trevor Watts. Watts’ latest opus, Veracity, contains 13 pieces for solo alto saxophone, providing ample scope to relish the magnificence of tone and wealth of colours he achieves. His extended techniques further broaden the palette, and the breadth of compositional ideas within which he contains his improvising ensures the music transcends any supposed limitations of listening to a single wind instrument for 50 minutes. Coltrane’s legacy lives on, and a proportion of the proceeds from Offering will help maintain his 1960s home in Dix Hills, New York.