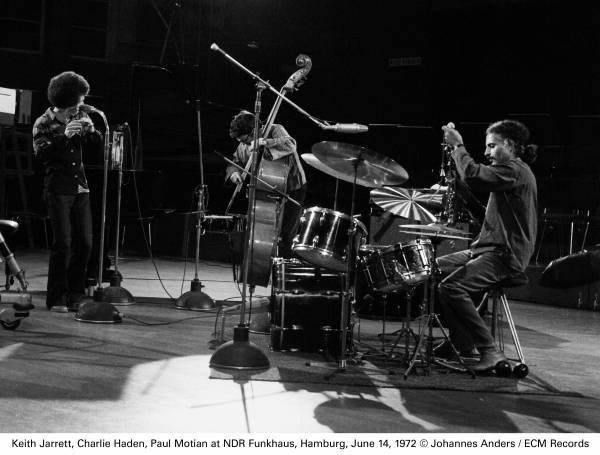

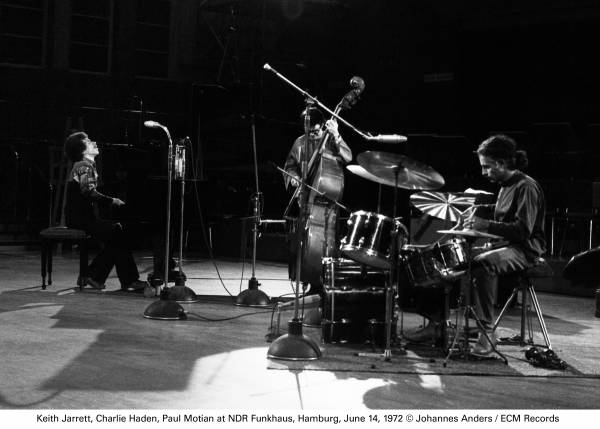

Keith Jarrett/Charlie Haden/Paul Motian: Hamburg ‘72 (ECM/Fuse)

Keith Jarrett/Charlie Haden: Last Dance (ECM/Fuse)

Jim Black Trio: Actuality (Winter & Winter/Birdland)

By the age of two he was singing professionally. “Yodelling Cowboy Charlie”, they called him. That was in the Haden Family Band, a star attraction on the US country music scene in the 1930s and ’40s. At 15 Charlie Haden contracted a form of polio that mangled his singing voice, so with mid-western pragmatism he switched to double bass, taking to it like a head to a cowboy hat. Less than six years later he was a crucial party to one of jazz’s most polarising revolutions.

By the age of two he was singing professionally. “Yodelling Cowboy Charlie”, they called him. That was in the Haden Family Band, a star attraction on the US country music scene in the 1930s and ’40s. At 15 Charlie Haden contracted a form of polio that mangled his singing voice, so with mid-western pragmatism he switched to double bass, taking to it like a head to a cowboy hat. Less than six years later he was a crucial party to one of jazz’s most polarising revolutions.

If it seems an improbable stylistic leap the fact is that the Family Band’s harmonies had been the perfect ear-training for Haden to improvise bass lines to run parallel to Ornette Coleman’s darting saxophone solos. The revolution, unleashed around 1959, was that Coleman’s music was created without underlying chord progressions.

That infant ear-training also made Haden one of the most in-tune players of an instrument on which even acclaimed practitioners can make minor errors of intonation. His ultimate asset, however, was his sound: a low gut-string thrum, so expressive and so replete with meaning that a single note could be an end in itself. Only two players in jazz history have charged a single note with so much music: Haden and Miles Davis. This is an infinitely more profound virtuosity than mere dexterity. You need a deep feel for why and how sound moves us.

I first heard this sound when living in one of those institutions tailor-made for expanding musical horizons: the group house. I, who had never even heard of Haden, was suddenly confronted by the deepest, fattest, roundest and most moving bass sound I had encountered. If the earth gods sang they would sound like this, and if I found it a little confronting at first I also had an instinct that most of what I had been listening to had just been made to seem frivolous.

I first heard this sound when living in one of those institutions tailor-made for expanding musical horizons: the group house. I, who had never even heard of Haden, was suddenly confronted by the deepest, fattest, roundest and most moving bass sound I had encountered. If the earth gods sang they would sound like this, and if I found it a little confronting at first I also had an instinct that most of what I had been listening to had just been made to seem frivolous.

Before the advent of jazz rock at the end of the 1960s that decade had produced four jazz bands whose influence continues to resonate half a century later: those of Coleman, Davis, Bill Evans and John Coltrane. Were a fifth to be added it might well be the Charles Lloyd Quartet, which included Keith Jarrett, the most precocious pianist of his generation. When Jarrett (who also played with Davis) formed his own group in 1967 he pulled together Haden (who, in addition to Coleman, collaborated briefly with Coltrane) and drummer Paul Motian, who after playing in the definitive version of the Bill Evans Trio, had joined the more radical, shape-shifting pianist Paul Bley (another Haden alumnus).

The ensuing Keith Jarrett Trio was, therefore, a super-group of sorts and possibly the most flexible band jazz had spawned. If Jarrett wanted a gospel groove Haden and Motian would build him a funky Baptist church; if he wrote a pretty ballad they would make it as tender as a kiss; if he wanted swinging bebop they would put skates under the piano. Whether Jarrett wanted to conjure up the sounds of the first Americans, improvise freely, experiment sonically or play country rock they could match him step for step in the chosen dance.

Now a hitherto unknown live recording, Hamburg ’72, has come to light and, being derived from German radio tapes, the quality is exemplary. The remastering job was undertaken the day after Haden died in July this year.

By 1972 the trio had actually become a quartet with saxophonist Dewey Redman, but for this tour he was unavailable, so say hello to one of the most magical documents of Jarrett, Haden and Motian in existence. Its crowning glory is the only known recording of Jarrett playing Haden’s folkloric masterpiece, Song For Che (the bassist being a committed communist in a decidedly antagonistic America).

In addition to piano Jarrett plays percussion, flute and, most importantly, his growling, half-vocalised soprano saxophone. Motian routinely opts for the least expected option, opening the music up in ways that made him such a pivotal figure until his death in 2011. Haden, meanwhile, is the rock upon which the group is built – although lava flow may be a more apt metaphor, given his warmth and capacity bend to any musical mould. Fans of any of these three master musicians will be enthralled by this extraordinary addition to the catalog.

This album is a much more fitting epitaph to Haden’s genius than Last Dance, a recently-released second instalment of duets he recorded at Jarrett’s home in 2007. As with its predecessor, Jasmine, something of the scale of the bassist’s sound has been lost in the recording, and the interest in the pair running through some standards is hardly in the same league as the anything-could-happen artistry of Hamburg ’72. Of course it is still good at being what it is, but the sights are set lower. This is intimate art capturing a singular rapport; music radiating a muted, candle-lit glow rather than showers of sparks.

Haden has had a profound influence on players the world over, including the New Yorker Thomas Morgan, who was Motian’s last bassist of choice. The fact that Morgan has grasped just what heft a single note may have can be heard in a striking new release from the trio led by drummer Jim Black, and completed by pianist Elias Stemeseder. As is typical of Black’s compositions, textural and rhythmic surprises abound.

4 stars