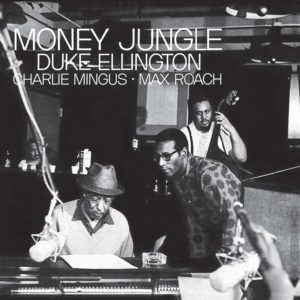

Charles Mingus didn’t want to do it. This was ’62, and he had a major project of his own on the boil; didn’t have the time. Of course he loved Duke Ellington: the man, his composing and his piano playing. Who didn’t? But it was Duke who’d fired him nine years before, and for what? He wasn’t really going to kill Juan Tizol with that axe. Just scare the bastard a little. Nonetheless the bassist eventually agreed to make the record. Duke could charm anyone into doing anything. Were he alive today he could charm Trump into gracious defeat.

Max Roach, by contrast, didn’t have to be asked twice. Max was open to anything. You heard that in his drumming. He’d never played with Duke, and to record with him would let him get inside the mind of jazz’s greatest composer. The trio didn’t rehearse; just met at Duke’s office the day before the session. Duke was warm, welcoming, self-deprecatory: “Just think of me as a poor man’s Bud Powell,” he said (Powell being the poster-boy for bebop piano virtuosity). He had a few tunes he’d like to try. Max enthused and Mingus, jazz’s second greatest composer, grunted. “A couple of them I’ve written especially with you boys in mind.” Even Mingus’s barrel chest puffed out a little at that, although he reiterated he didn’t have much time. “Three hours, max,” said Duke, and he and Roach grinned at the pun. They shook hands. Duke said how much he was looking forward to his first trio date in nine years.

As distinctive a pianist as he was, for 35 years his main instrument had been his orchestra. Born in 1899, Ellington, Stravinsky once said, was without peer among living composers, period. His father had made naval prints and been a part-time butler for the rich. This latter role was probably the source of the young Ellington’s taste for dapper clothes – which was why they called him “Duke”.

He didn’t write arrangements, he wrote parts for the personalities of his players. His band was like a vast keyboard in which each note was not just a different pitch, but a different take on humanity. Press Harry Carney’s baritone sax, and the most opulent sound in jazz history flowed out; press Cootie Williams, and a trumpet erupted that had all the urgency of a siren. Duke loved his band, and its members venerated his genius, graciousness and work ethic. Because they toured constantly, he wrote most of his thousand-odd compositions in cars, trains and hotels: fragments scratched on coasters and the backs of envelopes. He was never stuck for an idea; just for paper on which to write it.

Despite being a hero for Mingus and Max, he found making Money Jungle with them wasn’t easy. Duke, a generation older, didn’t exactly speak fluent bop at the piano, and Mingus and Max’s whole deal for the previous 15 years had been about moving beyond accompaniment; about equality of roles. Mingus had insisted on Max’s involvement, but since they’d last worked together Mingus had grown used to his own drummer, Danny Richmond, who’d developed a sixth sense for the bassist’s love of shifts in tempo, groove and dynamics.

During the recording a cantankerous Mingus suddenly packed up his bass and left. Ellington followed him, asking what was wrong. “Man, I can’t play with that drummer,” was the bassist’s reply – although the fact Duke hadn’t opted to include any Mingus compositions was probably bugging him, too. Duke soothed things over, and the session was completed. You can actually hear some of that tension, notably on the extremely agitated blues that is the title track. You also hear three giants searching out common ground in real time, finding it, and making some glorious music, with Ellington loosening up harmonically and rhythmically, and his spare, elegant style readily accommodating the others’ conversational approach. A highlight is the gorgeous Fleurette Africaine, on which Mingus plays with extraordinary invention across Max’s little mallet melodies.

During the recording a cantankerous Mingus suddenly packed up his bass and left. Ellington followed him, asking what was wrong. “Man, I can’t play with that drummer,” was the bassist’s reply – although the fact Duke hadn’t opted to include any Mingus compositions was probably bugging him, too. Duke soothed things over, and the session was completed. You can actually hear some of that tension, notably on the extremely agitated blues that is the title track. You also hear three giants searching out common ground in real time, finding it, and making some glorious music, with Ellington loosening up harmonically and rhythmically, and his spare, elegant style readily accommodating the others’ conversational approach. A highlight is the gorgeous Fleurette Africaine, on which Mingus plays with extraordinary invention across Max’s little mallet melodies.

Money Jungle streams on Apple Music and Spotify; on CD and LP from Birdland Records.