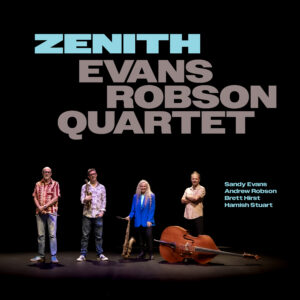

Zenith

(Lamplight)

8/10

Some people hate pigeons, but in flight a flock can mesmerise with their abrupt turns, take-offs and landings, without ever banging wings. How clumsy we seem, by comparison. Well, not all. Saxophonists Sandy Evans and Andrew Robson, bassist Brett Hirst and drummer Hamish Stuart can curl and twist around each other in musical flight, with a similar capacity to avoid collisions.

This is a key secret of jazz at its highest level: playing around each other, without needing constant points of convergence. The cause is aided in this band by the absence of a chordal instrument, and the consequent expanses of vacant space in the music’s midrange. Watussi Dreaming, for example, is just a bent blues in essence, but give it a polyrhythmic quality and more exotic scalar options, and suddenly, in the hands of these players, it becomes open-ended and unpredictable.

Even more open is Evans’ The Big Merino, which reminds me of something her beloved old band, Clarion Fracture Zone, might have played. Melodically zany, it lurches along over a half-time backbeat that Stuart unwinds behind the solos, so the horns are jerked and twitched like marionettes by the groove. Evans (on tenor) and Robson (baritone) respond with improvisations packed with whacky interval leaps and slurring asides, while Stuart’s subsequent solo is like the soundtrack for a slapstick routine.

Even more open is Evans’ The Big Merino, which reminds me of something her beloved old band, Clarion Fracture Zone, might have played. Melodically zany, it lurches along over a half-time backbeat that Stuart unwinds behind the solos, so the horns are jerked and twitched like marionettes by the groove. Evans (on tenor) and Robson (baritone) respond with improvisations packed with whacky interval leaps and slurring asides, while Stuart’s subsequent solo is like the soundtrack for a slapstick routine.

Then, to keep the surprises coming, suddenly there’s Robson proving to haunted school children everywhere what an iridescent instrument the descant recorder can be. The piece, his own Tea Horse Road – to these ears as evocative of Native American music as it is of the titular ancient Chinese trade route – rides on Hirst’s bouncy riff and Stuart’s shakers and hand-drumming, and has a skimming solo from Evans’ soprano.

Simpler rhythmic options are also embraced, as on Evans’ slow, soulful tribute to the late Archie Roach, For Archie. Here the bass and drums lay down a straightforward 3/4 groove, across which the saxophones testify like true believers, all preceded by Hirst offering one of his typically supple and heartfelt solos. For Archie also has a cousin in Robson’s lazy-day Lucky Jim, featuring the brawn of his baritone.

The boppish The Running Tide (by Evans) is reminiscent of Charles Mingus’ work, with its marvellous deployment of accelerations and decelerations. It boasts a seething, bubbling dialogue between the saxophones, before compelling solo statements from both bass and drums.

They end with the aptly titled Cry to the Waning Moon, which reinforces the impression that Hirst’s bass has never been better recorded, with sumptuous low notes and a singing tone higher up. Slow and lonesome, the melody is taken by Robson’s alto and harmonised by Evan’s tenor. This could well become my favourite composition on an album packed with strong ones from both leaders, and with a wealth of slippery dialogues between four master musical conversationalists.