Belvoir St Theatre, January 10

8/10

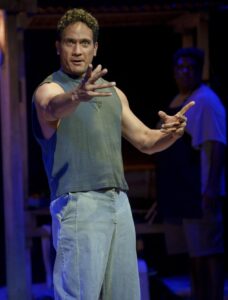

How do you dramatise a book composed of letters? Isaac Drandic and John Harvey had many solutions in adapting Thomas Mayo’s Dear Son, consisting of letters he asked fellow Aboriginal men to write to their sons or fathers, and more solutions were probably added by Drandic in his role as director. (He also bravely acted, book in hand, as a replacement for the sick Luke Carroll.)

Drandic and Harvey located the play in an outback men’s shed, strikingly designed by Kevin O’Brien and lit by David Walters. While each letter had a protagonist, the text was passed around the cast of five, with described scenes enacted (three actors even becoming a growling a V8 car!), blocks of text delivered in unison (to potent effect), and dance and song.

The resultant play, produced by Queensland Theatre Co and State Theatre Company South Australia, and presented by Sydney Festival, runs for only 70 minutes, yet seemed longer, not because it dragged, but because it’s crammed with mood swings. These range from broad humour to confessions, statements of love and onto a sinister vignette in Darwin’s notorious Don Dale Youth Detention Centre.

Given the book’s impact, I expected the play to be more harrowing, and perhaps it would be, were Carroll beside Jimi Bani, Waangenga Blanco, Kirk Page and Tibian Wyles, all of whom excelled.

Drandic, lacking the regular actors’ projection, handled Mayo’s letter to his son, which begins with regretting that when the son was nine and reached for his father’s hand in public, Mayo rejected the gesture, saying the son was too old for that. Wyles was the protagonist in Troy Cassar-Daley’s letter to his son, telling of the powerful love that conceived him.

Bani handled Yessie Mosby’s letter to his four sons, brimming with evocations of growing up on the Torres Strait’s Masig (Yorke Island). It was this piece that included the powerful dance sequence, choreographed by Blanco. Page took on Stan Grant’s letter to his boys about the suffering of his own father, who was visited in a dream by his ancestors as magpies, telling him it was not yet his time to die because he had a mission to save the Wiradjuri language.

The two funniest stories, Jack Latimore’s about trying to reach an uncle in Port Macquarie before he died, and Charlie King’s recounting of his father’s bicycle ride from Melbourne to Darwin (via the East Coast), were brilliantly delivered by Blanco and Bani, respectively. King’s, one of the finest contributions to book, ends with Bani expressing regret for not telling his father of his love and admiration before he died.

Setting aside grievances, embarrassment and rivalries to say the important things before it’s too late, and dealing with racism, are recurrent themes. The moving conclusion saw each actor address us as himself and speak of his own families. The collective warmth of heart vibrated through the theatre.

Until January 25.