Capitol Theatre, August 27

8.5/10

The best writers are clairvoyants. They pen a play, novel or even a musical that might have a contemporaneous or historical setting, yet it predicts the future by speaking to subsequent generations so precisely of their own time. Fred Ebb’s brilliant book and lyrics to Chicago (the book co-authored by Bob Fosse, the show’s original director and choreographer) may date from 1975 and be set in the 1920s, but they depict the current nature of celebrity and the short attention spans of media and consumers with crystal-ball prescience.

“You’re a phony celebrity, kid. In a couple of weeks no one will know who you are,” lawyer Billy Flynn tells murderess Roxie Hart, which could have had a certain irony with one of the leads, Casey Donovan, having reached stardom via Australian Idol, and another, Natalie Bassingthwaighte, having topped up her celebrity via reality television. In the event this is one of the happiest confluences of star-power and ideal casting I recall.

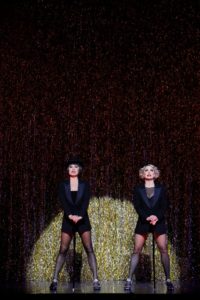

Crucial to a successful production of Chicago is striking a perfect symmetry in casting Roxie and Velma, so neither’s acting, singing, dancing or charisma outshines the other. Bassingthwaighte’s Roxie and Alinta Chidzey’s Velma are two black-mascaraed peas from the same pod, bringing their characters to vivid life: Chidzey a feline, vivacious Velma; Bassingthwaighte a cute, wicked, dumb Roxie. Neither steals the show in a company boasting such frightening talents as Haley Martin and Andrew Cook in the ensemble, but both more than enhance it.

So does Tom Burlinson as Flynn, ticking the boxes of urbanity, cynicism, presence and quality of singing, all with a silken touch. Donovan manages to make Mama Morton, the jailer, more warm-hearted than some depictions, while still conveying a don’t-mess-with-me edge, and she has the voice to shred When You’re Good to Mama. The ever-reliable Rodney Dobson is all class as Roxie’s put-upon husband, Amos, and makes the most of Mister Cellophane, a song in which Ebb and composer John Kander pull off the sublime double-act of spawning pathos and humour simultaneously.

As with the 2009 Sydney season, this production is based on the 1996 New York staging by director Walter Bobbie and choreographer Ann Reinking. The orchestra (here directed by Daniel Edmonds) constitutes the set by filling the upstage half of the playing area on a steep rake. It’s a masterful solution that not only physically places Kander’s unforgettable music – a pastiche of jazz and vaudeville – centre-stage, it also amplifies the show’s inherent Brechtian intent of exploding the fourth wall, and reminding us that we’re watching a vaudevillian version of a musical. Yet when fully pumped up with blood, lust, lies, dreams, greed and ambition as they are here, the characters (based on a 1920s book by Maurine Dallas Watkins) are entirely real, even as we see through them to the orchestra accompanying the songs that are their thoughts.

It was fascinating to see this 1970s ground-breaker only a week after West Side Story, the ultimate 1950s revolution in musical theatre. If you can only see one, this is the finer production, with dancing (supervised by Gary Christ) so crisp that it threatens to snap with every step. My only gripe is not with the production, but that Kander and Ebb, after landing so many knockout blows, could find no better Act One finale than the limp duet for Roxie and Velma that is My Own Best Friend. Still, can’t do much about that now.

Until October 20.