The presiding doctor at his death assumed he was between 50 and 60. Four possible causes of death were given: perforated ulcer, advanced cirrhosis, pneumonia and heart-attack. In fact Charlie Parker was only 34. In his brief career he’d burned brighter than any comet in the jazz firmament, and this not only took its own toll on his health, it catalysed self-abuse on a grand scale, at least in part because his pioneering art was sometimes ridiculed, and barely appreciated outside of a cognoscenti.

Many assumed he was called Bird because he sang like one on his alto saxophone, but the full nickname, “Yardbird”, was originally bestowed because of his passion for fried chicken. Lots of it. In fact Bird did nothing by halves in music or in life. Just as he was a glutton for food (even hamburger-eating competitions), he was a glutton for heroin, whisky and sex, as if he were wrapping himself in layers of insulation from a hostile world he couldn’t tame with his art. This made him reserved, suspicious, erratic and intuitive. As pianist John Lewis put it, “Bird was like fire. You couldn’t get too close.”

As an early teen he was laughed out of Kansas City jam sessions, so he wore out his Lester Young records learning to replicate the great tenor saxophonist’s solos. By the time he sat in on his first jam in Chicago, his playing stopped the room. He was 17. His inauspicious early New York gigs were in the Parisien Ballroom, where every dance tune was played at the same tempo, in the same key, and lasted for exactly 60 seconds – a soul-destroying routine that nonetheless instilled a vast repertoire in Bird’s vice-like memory.

His first recordings were for pianist Jay McShann, with whom he toured the South in 1941, and discovered the dark void of racism in the muzzle of a policeman’s sawn-off shotgun. By the time he left McShann he was lighting up jazz with solos of unprecedented incandescence. Only one jazz player was then universally considered a virtuoso: pianist Art Tatum. Having listened deeply to Tatum, Bird aimed for a comparable facility on the saxophone. Instead he raised the bar.

By 1942 he had the sound, speed, range and breath-control he needed, and was revolutionising jazz harmony, melody, rhythm and aesthetics into what became known as bebop. The odd screaming trumpet apart, pre-Bird jazz largely consisted of warm, rounded and rather elegant sounds for an elegant era. Parker’s alto was piquant, edgy and as urgent as a siren. Yet, for all his breakthroughs, he was also a traditionalist who loved the blues, and just happened to extract wider melodic options from the form. He could also temper his urgency with insouciance and, on ballads, a lavish tenderness.

By deploying bristling tempos and conveying a wider emotional palette, Parker (and the likes of Dizzy Gillespie, Max Roach and Bud Powell) changed jazz from dance music to listening music: a challenge to players and audiences; one that Bird counterbalanced with the euphoria of heroin. This numbed his treatment by racists; nullified the bad food and worse rooms on the road. But to a generation of young jazz artists Bird was the Pied Piper, and if he took heroin and played with such astonishing virtuosity and invention, then maybe if they, too dabbled… Many tested the theory, some dying or being jailed having come no nearer their god.

By deploying bristling tempos and conveying a wider emotional palette, Parker (and the likes of Dizzy Gillespie, Max Roach and Bud Powell) changed jazz from dance music to listening music: a challenge to players and audiences; one that Bird counterbalanced with the euphoria of heroin. This numbed his treatment by racists; nullified the bad food and worse rooms on the road. But to a generation of young jazz artists Bird was the Pied Piper, and if he took heroin and played with such astonishing virtuosity and invention, then maybe if they, too dabbled… Many tested the theory, some dying or being jailed having come no nearer their god.

When asked about his own religion, Bird replied, “I am a devout musician.” He died in 1955 in the home of the Baroness de Koenigswarter, a moneyed arts philanthropist who dabbled in painting, her materials including milk, whisky and perfume. In the entire jazz pantheon only Louis Armstrong’s revolution compares with the scale of Bird’s, which bred the innovations of Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman.

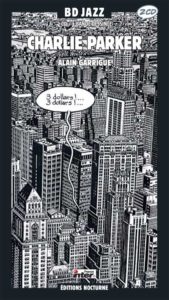

Among myriad compilations, BD Jazz’s Charlie Parker is an especially-well curated two-album set, which streams on Apple Music and Spotify.