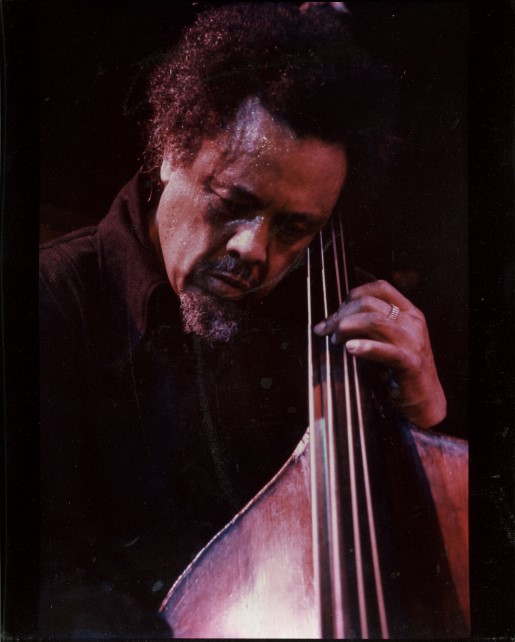

Perhaps he instinctively empathised because he, too, had been treated like dirt. That’s why he called his autobiography Beneath the Underdog. He, too, had had his music – some would say his genius – belittled. So when others shrugged their shoulders at the hopelessness, or openly mocked the man with the sad, empty eyes whose hands could no longer light up a piano the way they once did, Charles Mingus stood by Bud Powell.

Was it Bud’s fault he’d been beaten to a pulp by railway police, presumably for the crime of being black; beaten until the brain inside his cracked skull was never quite the same again? Was it Bud’s fault he was subjected to shock treatment, before they even knew the horrors they were inflicting? Was it his fault they medicated his schizophrenia with a drug that slowed the most virtuosic pianist that jazz had known?

Not that empathy was always Mingus’s strong suit. Duke Ellington fired him when the bassist attacked trombonist (and Caravan composer) Juan Tizol, because Tizol badmouthed Mingus’s sight-reading with a racial slur. Later, under pressure from the deadline for the most ambitious concert of his life, Mingus punched trombonist Jimmy Knepper, breaking his teeth and severely compromising his career.

Yet he composed with a tenderness to match Ellington’s, and expressed other feelings – fury, ecstasy – with unparalleled intensity. He stretched his imagination into places that jazz composers hadn’t visited before, and insisted his players memorise his complex charts, teaching them phrase by phrase, so on stage they weren’t staring at dots, but listening like hell, because he might cue an unexpected change at any moment. They worshipped him (despite calling his Jazz Workshop project the “jazz sweatshop”), because he extended their artistry. Only Ellington and Miles also brought out the best in so many brilliant musicians.

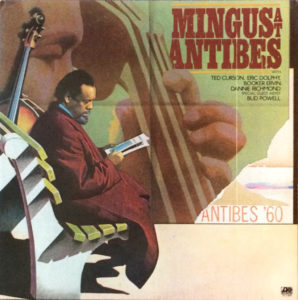

In 1960 Mingus was riding such a creative high that masterpiece albums seemed the only sort he knew how to make. In concert his band burned, as it did on July 13 at Antibes Jazz Festival in France, where a live album was recorded that also documented the last time Bud Powell and Charles Mingus played together.

Bud and his wife Buttercup were Paris-based by then. They couldn’t stop the headaches, schizophrenia or drinking, but in France they could evade the racism. So when Mingus took a piano-less quintet to Antibes he invited Bud to join them for April in Paris, a song that would put Bud in his comfort zone. The result is sad and exhilarating all at once, because on the one hand you hear Bud’s articulation like a blurry shadow of its former self, but on the other you still hear the courtly elegance of his lyricism, and you hear Mingus willing him on – not verbally as he does with his band, but subtly, from the bass: making that comfort zone so big and fat that Bud knew he would bounce if he fell off the racing chords.

Bud and his wife Buttercup were Paris-based by then. They couldn’t stop the headaches, schizophrenia or drinking, but in France they could evade the racism. So when Mingus took a piano-less quintet to Antibes he invited Bud to join them for April in Paris, a song that would put Bud in his comfort zone. The result is sad and exhilarating all at once, because on the one hand you hear Bud’s articulation like a blurry shadow of its former self, but on the other you still hear the courtly elegance of his lyricism, and you hear Mingus willing him on – not verbally as he does with his band, but subtly, from the bass: making that comfort zone so big and fat that Bud knew he would bounce if he fell off the racing chords.

For the rest of the 70 minutes your ears are pinned back by a great ensemble blazing with comet-like intensity on a Mingus repertoire that managed to gaze into jazz’s past and future simultaneously. There’s Danny Richmond, the bassist’s partner in the art of swing; the drummer who for 20 years telepathically knew when Mingus was going to change rhythmic direction mid-stream. Then there’s Booker Ervin, among the most sophisticated of the bruising Texan tenor players, and Ted Curson, the perfect Mingus trumpeter. And finally there’s Eric Dolphy, who revolutionised the alto saxophone, the bass clarinet and jazz improvisation more generally; who was as incandescent as Greek fire was in pre-medieval warfare.

Together they lit up such Mingus classics as the fervent Wednesday Night Prayer Meeting, Folk Forms 1 and the joyous Better Git Hit in Your Soul; compositions by a man whose points of reference ranged from the field hollers of slavery to Charles Ives. Jazz has only spawned a handful of geniuses. We lost one when Mingus died in 1979.

Mingus at Antibes streams on Apple Music and Spotify; on disc from Birdland Records.