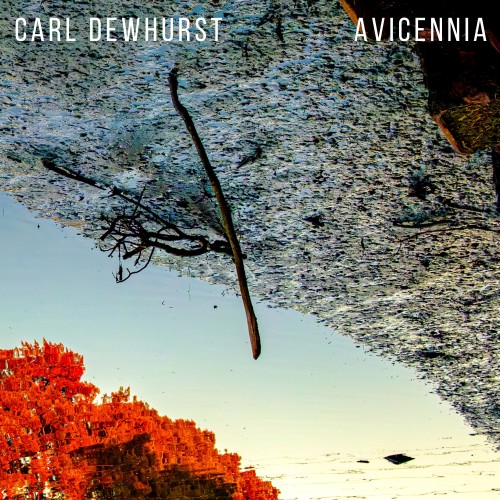

Avicennia

7.5/10

Carl Dewhurst is among the great chameleons of Australian music. Were each of the manifold projects in which he’s been involved across the last 30 years to be played in adjacent rooms off a long corridor, every time you opened a new door you’d swear you heard a different guitarist. He has variously sounded a little like Buddy Guy, Alan Holdsworth, Wes Montgomery, Fred Frith and Niles Rodgers, without ever directly imitating any of them. More often he has sounded like no one else at all, having developed unique approaches and techniques. This originality seeps organically through the cracks between the diversity of idioms in which he plays guitar.

Avicennia presents his current trio, with long-term collaborator Cameron Undy on bass and newish drummer Alex Inman-Hislop, plus guest saxophonist Linda Parrott. It’s also a reunion of sorts: Dewhurst, Parrott and Undy first teamed up in 1993 with maverick drummer Louis Burdett as NUDE, which performed for some years, before Parrott moved to New York for the next quarter-century. There she was in the kitchen where jazz was broiled and baked, playing with several big bands and artists as diverse as Diane Schuur, Nancy Wilson and Cindy Blackman. Now she’s now back in Oz.

The album investigates Dewhurst compositions (and a reinvention of Charlie Parker’s Ornithology) lying well outside the old NUDE remit of drawing on Ornette Coleman’s harmolodic concept. This is melodically much slinkier music, often built on mind-spinning rhythmic puzzles. Undy exclusively plays electric bass, with that luxurious, thick-pile sound of his, and Inman-Hislop, while applying his instincts for crispness and spaciousness, is executing Dewhurst-conceived grooves that are often inherently jittery and unsettled, and which he sometimes further cleaves with jagged fills.

Although the music is mostly understated, its restlessness – the gorgeous Resonance of a Smile and Tempe Sarabande apart – generated by the metrical surprises sustains a distinctive tension. Some tracks, such as the lively A Night in Turella, are performed in trio format, but the band inevitably has a broader expressive range when fleshed out with Parrott’s alto, on which she obtains a sound so dry that you’d swear each note’s been sandblasted before it leaves the bell. This lends an emotional ambiguity to her lines, which is also a hallmark of Dewhurst’s playing, ensuring sentimentality is an entirely foreign realm.

Dewhurst’s choice to use largely with the same guitar sound throughout is mildly curious. He has such a vast array of textures and effects at disposal, and some songs, such as the closing Drainpipe Blue feel like they’re crying out for a blast of dirty, back-alley distortion (hinted at on the lurching Buster Brown), that really pins you back by the ears, even if only for a few bars of contrast. Perhaps, given the rhythmic complexity, other aspects of the music were conscious exercises in restraint – given we inhabit a world that champions excess in all areas.