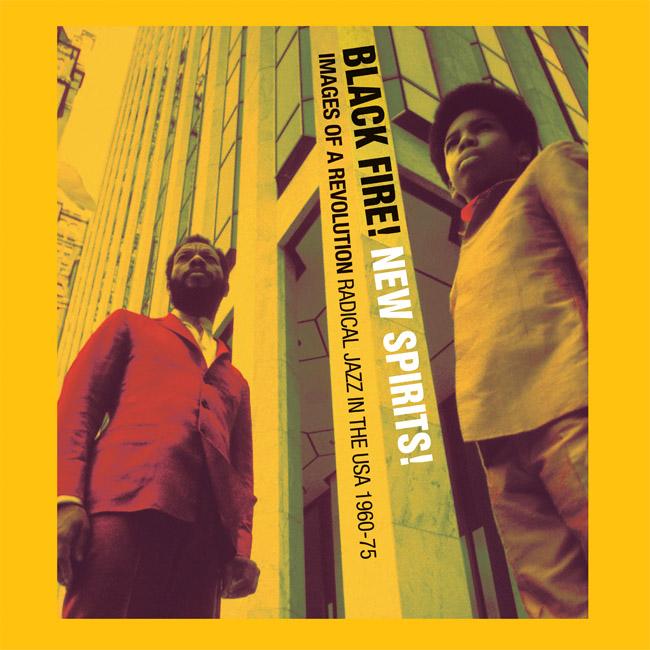

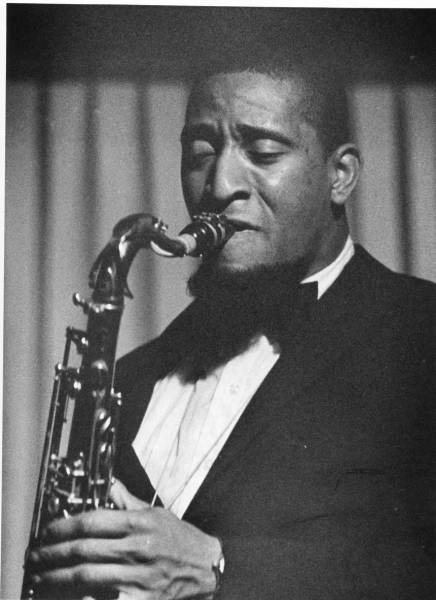

At 83 Sonny Rollins remains a tall man. In the 1960s he was positively imposing, a quality echoed in the sound of his tenor saxophone. His chin sprouted a tufty little beard at this time, and this combined with his hooded eyes and size to imply a monumentalism and impassivity reminiscent of the Pharaohs. There was also a note of defiance in his expression and his playing, a recurrent quality through scores of photographs of jazz musicians in a new book called Black Fire! New Spirits!, with the joint subtitles of Images Of A Revolution and Radical Jazz In The USA 1960-75.

At 83 Sonny Rollins remains a tall man. In the 1960s he was positively imposing, a quality echoed in the sound of his tenor saxophone. His chin sprouted a tufty little beard at this time, and this combined with his hooded eyes and size to imply a monumentalism and impassivity reminiscent of the Pharaohs. There was also a note of defiance in his expression and his playing, a recurrent quality through scores of photographs of jazz musicians in a new book called Black Fire! New Spirits!, with the joint subtitles of Images Of A Revolution and Radical Jazz In The USA 1960-75.

The ’60s are so often depicted in terms of mass-impact pop groups, drugs, the sexual revolution and the protest movement, perhaps sprinkled with a little dawning Eastern mysticism. But for African Americans the period was defined by a growing militancy in the struggle for civil rights. The music that reflected this was not the happy-go-lucky grooves and tunes of Motown, but the terrible beauty of a new breed of jazz.

This was music that was not afraid to express frustration and even to rage in anger. It may have been deeply rooted in jazz, but elements of the sonic experimentalism of twentieth-century European art music crept in, as did influences of Indian music and, most importantly, the African culture that was the players’ pre-slavery heritage.

One instrument expressed the era’s turbulence better than any other: the saxophone. In the hands of players like John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, Archie Shepp, Pharoah Sanders, Eric Dolphy, Charles Lloyd, Albert Ayler, Joseph Jarman and Roscoe Mitchell the saxophone proved the perfect device for communicating squalls of fury and passions as vast as those of the Greek tragedies.

Rollins was an influence on all the above, and the first to establish a direct connection between jazz and the civil rights movement with his stunning 1958 recording The Freedom Suite, an album re-released within a four-disc box-set, The Contemporary Leader, covering his output from 1958-62. The 6/8 rhythm of the suite’s middle movement carries a direct echo of Africa, while the album sleeve bore an overtly political statement from Rollins: “How ironic that the Negro, who more than any other people can claim America’s culture as his own, is being persecuted and repressed, that the Negro, who has exemplified the humanities in his very existence, is being rewarded with inhumanity.” Two years later Max Roach, drummer on The Freedom Suite, released his own masterpiece of civil rights militancy, We Insist! Freedom Now Suite.

Rollins never fully engaged with the torrential musical freedoms unleashed in the ’60s, and nor were all the artists who did overtly combative in their stance. Many preferred to deal in metaphors. Charles Lloyd (who swapped from alto to tenor because of Rollins and Coltrane) evolved an approach during the 1960s incorporating Eastern and African elements that was to appeal to the emerging hippy culture on a scale that no other jazz band replicated. A 1967 album was even called Love-In, and included compositions with titles like Tribal Dance and Temple Bells. A new DVD documentary about Lloyd, Arrows to Infinity, reveals just how influential Lloyd’s quartet (which included a young Keith Jarrett) was on not just other jazz players, but such rock bands as the Doors, the Band and the Grateful Dead. His 60s output was less often the music of anger than of healing, however, crowned by the gently keening, woody magnificence of his tenor saxophone sound.

The documentary has stunning concert footage and interviews with a huge array of musicians, including the man, himself, who these days exudes an almost saint-like benevolence. Pianist Herbie Hancock describes Lloyd’s playing as “cascades of sound that almost had an environmental aspect to it”. Where Coltrane testified with the zealous conviction of a Martin Luther King oration, Lloyd made and continues to make improbable musical dreams. In the ’60s he was the direct link between Black Power and the White love/drugs/mysticism/protest revolution. He himself went from believing the drugs were fuelling his creativity to eventually having to confront the fact that they were impeding it. Long periods of retirement resulted, leading to a “new” career in the last 25 years that has actually spawned his most profound work.

The documentary has stunning concert footage and interviews with a huge array of musicians, including the man, himself, who these days exudes an almost saint-like benevolence. Pianist Herbie Hancock describes Lloyd’s playing as “cascades of sound that almost had an environmental aspect to it”. Where Coltrane testified with the zealous conviction of a Martin Luther King oration, Lloyd made and continues to make improbable musical dreams. In the ’60s he was the direct link between Black Power and the White love/drugs/mysticism/protest revolution. He himself went from believing the drugs were fuelling his creativity to eventually having to confront the fact that they were impeding it. Long periods of retirement resulted, leading to a “new” career in the last 25 years that has actually spawned his most profound work.

While New York was the jazz Mecca, vital developments occurred elsewhere, most notably in Chicago, where the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) was formed on the down-at-heel South Side in 1965. Among the founders was another radical saxophonist and conceptual revolutionary, Roscoe Mitchell, who in 1969 co-formed the extraordinary Art Ensemble of Chicago (AEC). The AEC emphasised its African heritage to the extent of three members wearing elaborate costumes and painted faces. Rather than calling what they did “jazz”, they preferred “Great Black Music”, with the aphorism “ancient to the future”.

Despite the deaths of two members the AEC endures 45 years later, and Mitchell continues to pursue diverse projects under his own name, such as the new Conversations II. This has him playing most of the flute family and most of the saxophone family (including the floor-shaking bass saxophone) in company with Craig Taborn (piano, organ, synthesizer) and Kikanju Baku (drums, percussion). Here the anguished energy of the 1960s continues to burn (as it does in St Louis) in a series improvisations so dense that it is like peering through the layers of paint of a Jackson Pollock painting. Its very relentlessness is thrilling, independently of the high levels of invention, but it is assuredly not for the faint-hearted!

Sonny Rollins: The Contemporary Leader (Proper/Planet)

Charles Lloyd: Arrows To Infinity (ECM/Fuse)

Roscoe Mitchell: Conversations II (Wide Hive/Planet)

Black Fire! New Spirits! (Soul Jazz Books)