Billie Holiday: The Centennial Collection (Columbia)

Cassandra Wilson: Coming Forth by Day (Sony)

Ben Goldberg: Orphic Machine (Bag)

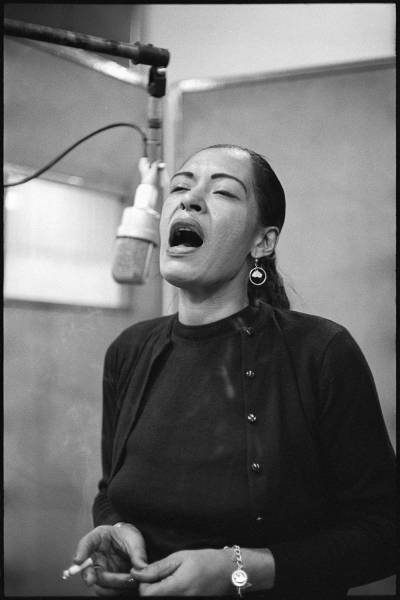

How did a woman with a smallish voice and modest range come to be celebrated as one of the twentieth century’s greatest singers? It seems unthinkable in the era of TV talent quests, when gaucheness, melodrama, shouting, exaggerated vibrato, ugly tone and vein-bursting effort are championed. But then Billie Holiday oozed genuine humanity and authenticity, a world away from all the ludicrously over-dramatized TV screeching. She not only transcended her jazz-singer peers, she transcended idiom.

This year is the centenary of Holiday’s birth. She was dead 44 years later, having created some of the world’s most beautiful music despite enduring a life harder than most could weather.

She was the offspring of teenaged sweethearts, and her birth was her musician-father’s cue to flee, leaving Holiday to spend her childhood as a ping-pong ball batted between relatives. At 10 she was raped and at 14 she was jailed for prostitution. In adulthood she lurched between abusive relationships, and began to lean firstly on alcohol and then heroin. In 1947 she was jailed for nine months for narcotics possession, after which, in a cruel double-hit, she was banned from playing in New York’s clubs. Even on her death-bed in hospital she was again arrested for possession and died in hand-cuffs. Along the way she was ripped off by record companies and poorly served by lawyers.

It is no wonder that she sounded convincing singing a harrowing lyric, or that her eyes were often sad, even in photographs where she was smiling. But if a harsh life were the sole ingredient for making superlative singers the world would be crawling with them, and it assuredly is not. So what made Holiday so great?

First and foremost she radiated an inner beauty that was echoed by the gardenias often decorating her hair. Then she had a quality that delineates all the best musicians: phenomenal feel for rhythm. For a singer this means a note-by-note instinct on how long to extend a vowel and which consonants to clip or even crunch. Holiday was better at this than any singer ever recorded, having an elasticity that leant her phrasing a sense of groove independently of the accompaniment.

Her other great strength was that she never fell into the all-too-common trap of self-consciously emoting. Any intensity at the core of a lyric and the passion at the core of her being was communicated organically, more like an instrumentalist than a singer, so her glissandi were imbued with a unique yearning quality, while the lyrics she sang always sounded fresh-minted.

She could add artistic gravitas to relatively modest songs like What A Little Moonlight Can Do, and could denote irony with a sonic arch of an eyebrow. Her ability to underplay a lyric was at its best on Gloomy Sunday, and even more on her ultimate masterpiece, Strange Fruit, the song she co-wrote in 1939 about African Americans being lynched in the “gallant South”.

In her final years when her voice was partly eroded like some ancient monument the emotional intensity only deepened. The best musicians loved working with her until the end, and magnificent tenor saxophonists like Lester Young and Ben Webster were drawn to her like bees to honey.

Although Holiday’s career may well have spawned more compilations than just about any other artist, the one that Columbia has released to celebrate her centenary is particularly well-chosen, except for its lack of anything from her last decade.

Holiday’s centenary has also spawned a tribute album by one the finest contemporary singers, Cassandra Wilson. On the surface the pair could not be more different: where Holiday’s voice was pitched high and had a keening quality Wilson’s is low, sensual and assured. Nonetheless they share two vital qualities: intimacy and understatement.

Of course Wilson is too sophisticated to actually emulate Holiday on a program of songs by or associated with her. Instead the approach adopted (in conjunction with producer Nick Launay of Nick Cave fame) was to shine a fierce light on the lyrics, and then see what musical responses were suggested. The upshot is that the songs are mostly kept sparse and raw, within the Mississippi roots style that is Wilson’s heritage – a quality that remains intact even when lush strings arrive as unexpectedly as an unlooked for puff of air on a sweltering day.

Central to the sound are Thomas Wydler’s drum parts, which are spare, simple and dripping with jungle-like humidity, and Kevin Breit’s guitar contributions which, whether percussive or ringing, always add mystery. Melting across these is Wilson’s contralto: breathy, thick, relaxed and illuminating the lyrics in ways that change the shadows of the words.

To suggest that Carla Kihlstedt is directly influenced by Holiday would be drawing a long bow, given her background is as much in art music and the avant-garde as anything that might be called jazz. Yet there are times on clarinettist/composer Ben Goldberg’s new album when Kihlstedt’s phrasing, timbre and lack of artifice do carry echoes of her great predecessor. The album is as hugely engaging as it is genre-bending, with breezy melodies, inventive lyrics and a cast that includes trumpeter Ron Miles, pianist Myra Melford, guitarist Nels Cline and bassist Greg Cohen, and with Kihlstedt playing violin as well as singing with such exquisite restraint.

4 stars