Saxophonist Bernie McGann was once hired by a juggler, who tossed him some sheet music, counted in the tune and began juggling. McGann didn’t play a note; just stood staring at the music, knowing he shouldn’t have come. The juggler needed McGann, but McGann didn’t need the juggler. He could keep endless ideas spinning in the air as it was.

Yet he couldn’t chase what he heard in his head while playing in clubs or big bands, let alone with a juggler. If he couldn’t get gigs that let him do things his way, he’d rather live in Bundeena, rise at dawn, work as a postie in Cronulla, and have the afternoons to practice in the Royal National Park.

Although those who worked with him in the early ’60s say his sound – the most instantly recognisable in Australian jazz – was then already in place, McGann was unimpressed by these early tapes. For him it was after the Bundeena practice phase that both sound and ideas began to align the way he wanted – from the mid-’70s on. One moment he could conjure the squeaks and rasps of native birds, then melt your knees with beauty, or from a matted tangle of jubilation and despair, rush up to a jaunty trill. He played the alto as though he’d meant to buy a tenor; as if the instrument were a life-long smoker, or the notes were sandblasted before they jostled from the bell: gruff, gritty, coarse-grained and intensely human. Sometimes a Cubist, McGann investigated a motif from multiple perspectives simultaneously, with improbable interval leaps and constant shifts in timbre, velocity and mood.

The originality was so startling that, this being staid old Oz, he was royally ignored: an outsider – not just too alien for the mainstream, but cold-shouldered by the jazz establishment, too.

After 40 years of banging his head against that wall of apathy, it suddenly burst in 1997, and McGann, about to turn 60, was engulfed in a torrent of acclaim. In two golden months he won an ARIA for best jazz album (Playground), led the first Australian trio at the prestigious Chicago Jazz Festival, had a biography published (Geoff Page’s Bernie McGann… A Life in Jazz) and won the Don Banks Music Award. He was the first jazz player to receive this latter $60,000 acknowledgement of “sustained and distinguished contributions to Australian music”.

His late-career rush of albums included Bundeena (2000), the breeziest he made with his trio of bassist Lloyd Swanton (of the Necks and catholics fame) and drummer John Pochee, whose own highly idiosyncratic playing had spiralled through bands that either he or McGann had led during those 40 years.

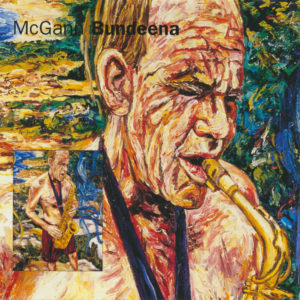

On the unmistakably McGann-penned Mr Harris the saxophonist smears ideas on the musical canvas as thickly as George Gittoes does paint on the album’s cover image, while the collective rustle of colours and textures is like being sonically brushed by foliage. Swanton’s Blues on the Prairie goads McGann into altissimo cries and bleats as well as supreme bottom-end articulation, and Maianbar, named for the village adjacent to Bundeena, is somehow exotic: a dish with a foreign spice, and with McGann tenderly draping lines across the rhythm section’s restraint. The Last Postman, more a lament than a ballad, has gorgeous bass harmonies, and his alto never more resembling a tenor. The hell-for-leather Venus and the Dogstar boasts full-throated exchanges with the drums, before McGann mostly saunters through The Varkarsians in the alto’s upper range, where prettiness and anguish mingle: a nettle in a posy of flowers. Let’s Tangle exemplifies Pochee’s ability to pump air into a groove, so the saxophone rides on a gust of wind rather than solid matter, and on the slow grind of Dirty Dozen the horn huffs and puffs and growls like a bear, before nonchalantly sliding up to those ephemeral smoke-rings of sound.

On the unmistakably McGann-penned Mr Harris the saxophonist smears ideas on the musical canvas as thickly as George Gittoes does paint on the album’s cover image, while the collective rustle of colours and textures is like being sonically brushed by foliage. Swanton’s Blues on the Prairie goads McGann into altissimo cries and bleats as well as supreme bottom-end articulation, and Maianbar, named for the village adjacent to Bundeena, is somehow exotic: a dish with a foreign spice, and with McGann tenderly draping lines across the rhythm section’s restraint. The Last Postman, more a lament than a ballad, has gorgeous bass harmonies, and his alto never more resembling a tenor. The hell-for-leather Venus and the Dogstar boasts full-throated exchanges with the drums, before McGann mostly saunters through The Varkarsians in the alto’s upper range, where prettiness and anguish mingle: a nettle in a posy of flowers. Let’s Tangle exemplifies Pochee’s ability to pump air into a groove, so the saxophone rides on a gust of wind rather than solid matter, and on the slow grind of Dirty Dozen the horn huffs and puffs and growls like a bear, before nonchalantly sliding up to those ephemeral smoke-rings of sound.

Never one for analysing or philosophising about music too much, McGann nonetheless thought about it deeply. Just non-verbally. We lost him in 2013.

Bundeena streams at https://berniemcgann.bandcamp.com/album/bundeena; on disc from Birdland Records.