So effective was he with his fists that they called him “The Brute”. Then you heard him play, and his opulent, breathy tenor saxophone sang of tenderness, loneliness and romance. In the yawning chasm between these extremes lies that fact that big, mean drunks can also be gentle giants. And, eventually, music, age and, yes, booze all blunted Ben Webster’s belligerence completely.

As long as someone bought him a drink, the tempo wasn’t too fast and the pianist didn’t crowd his solo, then he could push his trilby a little further back on his head, slump a little more in his chair, put his horn in his mouth and make high art as casually as if he were playing cards. Where most wind players shoot for a clean, sharp-edged sound, their breath indiscernible, Ben’s notes fluttered and whooshed with the air that had been warmed by his big lungs next door to his bigger heart. His delivery could almost seem lazy, were it not brimming with masterstrokes of phrasing, intensity, colour and dynamics. Nor was any sound as calming and moving simultaneously as Ben’s.

His great friend Lester Young played so lightly it seemed his tenor had shrugged gravity aside. Ben played like the large, lumbering man he was, but dared to reveal all that was concealed behind the heavily lidded eyes and heavier drinking: the sadness and bottomless capacity for loving music.

It was the romantic in him that put him in tune with Duke Ellington, whom he joined in 1940, and who eagerly began writing for him. When they hit the studio with Cottontail, Duke told the engineer to record a run-through that he assured the band was just a rehearsal, and then smilingly back-announced it was a take. Big Ben was livid, appraising what he’d just played – one of jazz’s most celebrated solos – as “lackadaisical”.

He’d come to the tenor unusually late, at 21, via violin, piano and alto. He started violin at eight (in 1917), hating it because other kids called him a sissy. He preferred piano, which he taught himself when his mother was out. His first gigs were as a pianist, and he was 19 before he played alto, picking up a gig when not even owning an instrument. On tenor he imitated his hero, Coleman Hawkins, until he found his own rounder sound by ’38, and then was ready for Ellington, an experience he described as his “PhD”.

He’d come to the tenor unusually late, at 21, via violin, piano and alto. He started violin at eight (in 1917), hating it because other kids called him a sissy. He preferred piano, which he taught himself when his mother was out. His first gigs were as a pianist, and he was 19 before he played alto, picking up a gig when not even owning an instrument. On tenor he imitated his hero, Coleman Hawkins, until he found his own rounder sound by ’38, and then was ready for Ellington, an experience he described as his “PhD”.

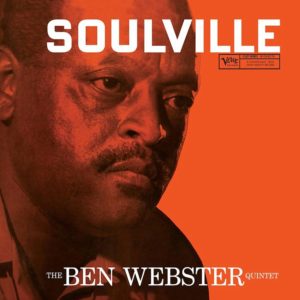

In 1950, his “brute” side rampant, he spent two years recuperating with this mother in LA. The LP’s invention then liberated Ben from the fleeting solos of 78 rpm records, giving him time to soften notes with fluffy, broad vibrato, and become the ultimate interpreter of ballads. The albums where he exclusively plays ballads (such as the provocatively titled Music for Loving) can become a feast of endless desserts, however. A better option is 1957’s Soulville (with pianist Oscar Peterson and a cracking band), where one can also savour a blues with a bit of grit, or some growly swing, such as a bear might have made. No sound epitomises jazz more than Ben’s tenor on Lover Come Back to Me, and the way he phrases the melody – the placement of rests and accents – is like watching Leonardo at work.

In 1964 he moved to Europe, mostly living alone. If he wasn’t touring, he’d sit in his flat, drink, listen to music and play his horn. His body clock ceased to recognise night and day: just sleeping and waking. Sometimes he’d drink for days, although he’d straighten himself up for a reunion with Duke: shoes shined, hair dyed, punctual.

In 1964 he moved to Europe, mostly living alone. If he wasn’t touring, he’d sit in his flat, drink, listen to music and play his horn. His body clock ceased to recognise night and day: just sleeping and waking. Sometimes he’d drink for days, although he’d straighten himself up for a reunion with Duke: shoes shined, hair dyed, punctual.

At a 1953 Amsterdam gig he drank so heavily that he actually spoke to the audience – for the first and last time. Driven home in Steve McQueen’s car, he didn’t survive the night. Having played the same horn since 1938, Ben decreed no one should play it after his death. He also decreed his ashes should be scattered to the air – the same element that defined his sound.

Soulville streams on Apple Music & Spotify; on disc from Birdland Records.