York Theatre, January 21

7.5/10

Originally from Nigeria, playwright Inua Ellams has said that he was born a man, and it was only when he moved to the UK that he became a “black” man. Such profound issues of personal identity, migration, race and racism intermingle with geopolitics, jokes, tall stories, concepts of masculinity, petty squabbles and football (on an imaginary TV) in Barber Shop Chronicles, much as the cut hair of many customers is swept into the same pile.

Initially the play seems to be a series of unrelated vignettes set in barber shops in London and various parts of Africa, but, as it develops across its 110 minutes, links are made, commonalities occur and characters are defined. The barber in each setting emerges as part confidant, part confessor and part style-council; a sounding-board and an adviser; a man who can make another man feel comfortable about being just a little pampered for a short time in a hard day.

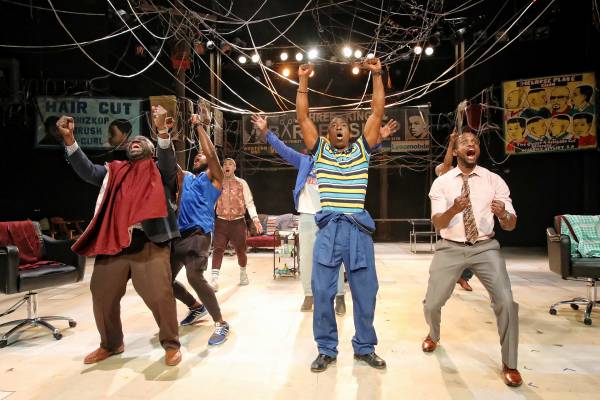

Directed by Bijan Sheibani the 12 members of the cast (in this National Theatre production) charge the stage with energy in the brief bursts of chanting and dancing that break up the vignettes. The dialogue, meanwhile, displays pressure-cooked testosterone, knockabout conviviality, male competitiveness and suppressed emotions, like so many pictures of different haircuts.

Ellams’ voice is commendably absent as his characters speak. Robert Mugabe is discussed as both hero and villain, and if a character in a Johannesburg barber’s decries Mandela’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission as having denied South Africa’s people the right of retribution for 350 years of oppression, you have no sense of whether Ellams sides with him or with the contrary case. That same character walked out on his baby son a decade and a half earlier, and now that baby son is a wannabe actor in London auditioning for a role in a play as “a strong black man” – while still being confused as to what that means.

Ellams, who is also a poet, writes short-hand dialogue full of musical cadences. Its delivery on the thrust stage of the York Theatre had its problems, however. Where we were sitting (close to the front, to one side) many lines by actors facing away from us were lost, a problem that may perhaps have been solved by some ambient microphones. (If you haven’t already booked, opt to sit in the middle.)

The most frequent setting, a London barber shop, is run by Emmanuel (Cyril Nri), whose easy-going nature is tested when accused by Samuel (Bayo Gbadamosi) of having had a hand in robbing Samuel’s father of the business. Like an image coming into focus as you draw closer, this gradually emerges as the pivotal plot-line that leads towards climax and resolution. Intergenerational friction and father-son relationships are rocky outcrops in this particular sea, and reality readily becomes clouded with myths. As one barber says, “The older a man gets, the faster he could run as a boy.”

Other discussions we eavesdrop upon include the relative appeal of black women and white women, the use of terms like “black”, “nigger” and “negro” and fathers who beat their sons.

A layer of anger pervades the work, but it is no more prominent than the layers of camaraderie, confusion, humour and sadness among the engaging characters, realised by a strong ensemble (most of whom play multiple roles). While hardly a masterwork, the play uncovers with a thick matt of issues and ideas that keep it buzzing in the ears like shears long after the final bow.