A teenaged Renee Geyer had just recorded her first album in 1972 when the band with which she made it, Sun, fired her for not taking the music seriously enough. Her subsequent career soared to the forefront of Australian popular music, while Sun died within two years. But if that looks like Geyer, one, Sun, nil, it’s not quite so straightforward. Sun had set its sights on a musical plane where jazz, rock, free improvisation and hippy idealism all converged. Geyer already had her heart set on soul music.

For those besotted at that time with the cross-genre explorations of the likes of Frank Zappa and the electric Miles Davis on one side of the Atlantic, and The Soft Machine, Matching Mole and some King Crimson on the other, Sun was a revelation: the first local band to embark on comparable sonic adventures, buttressed by the improbable power and depth of Geyer’s voice.

After seeing them on ABC TV’s GTK music program in 1972, I first them live in 1973, by which time Geyer had by been replaced by Starlee Ford’s startling contralto and vivacious presence. It was one of those gigs you never forget: compared with the era’s pervasive plodding rock, Sun made the possibilities seem limitless.

When the band folded in 1974, the only tangible relic was that lone album with Geyer – until now, when a four-disc set of rehearsal recordings has emerged. This shows Sun and its three successive singers (Ian Smith, Geyer and Ford) dashing between idioms, and offers glimpses of a Geyer on some of the freer pieces that we’d never hear again.

“I now know that it’s great for a singer to start with that sort of training,” she said in her autobiography, Difficult Woman. “Whenever I go out and do what I do in front of strangers, I’m aware that that background has helped me in terms of my lack of inhibition.”

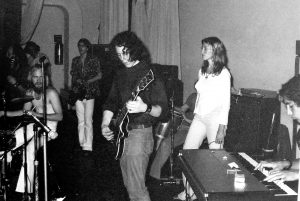

Saxophonist Keith Shadwick, bassist Henry Correy and drummer Gary Norwell were the constants in a band that variously included electric pianist George Almanza and guitarists Chris Sonnenberg and Tony Slavich. In Difficult Woman, Geyer dismissed her colleagues – especially Shadwick and Norwell – as reaching beyond their abilities. These being rehearsals, there are minor mistakes from all, yet there’s also a unique tension in the music – music which tends to work best when more atmospheric. Shadwick plays some incendiary tenor, while his flute offers pretty swirls of early-’70s mysticism, and Norwell exhibits a flair for enunciating a fluid blend of jazz and rock. Geyer may have sung with more accomplished players, and certainly with slicker ones, but I’m not sure she sang with many who had set their sights quite so high in the creativity cosmos.

Shadwick’s Tomorrow Has Gone is a free-jazz gem, and his sound on Pharoah Sanders’ Hum-Allah-Hum-Allah-Hum-Allah could peel paint off walls. The band’s rock side (I Thought I Knew My Mind), meanwhile, was heavily laced with the period’s psychedelia. Once one has leapfrogged a dodgy spoken-word introduction, Mindless Persuasion also casts a spell, and is among the pieces to include Soft Machine-like fuzz bass playing from Correy. More modest offerings include the meandering When I Reach out for Your Hand, and Sea of Tranquility, which can’t escape its hippy haze.

Unlike several of England’s jazz-tinged progressive rock bands, Sun was never let down by its vocals. Smith sings with devil-may-care freedom in the period when the band ranged across covers of Sanders, John Coltrane, Alice Coltrane, Nat Adderley and Max Roach – hardly material a conventional jazz band of the time would have performed. Ford was less self-conscious than Geyer about throwing herself into the improvising, and her improbable range is fully displayed on Lonely George.

With Geyer, you hear the tug of war between her R&B comfort-zone and the freer, jazzier, moodier pieces. The two can converge brilliantly, however, as on Sonnenberg’s haunting The Message, with Geyer diving to the depths of her range, and singing with such bruising power as summons a sudden blazing guitar solo. She’s in her element wailing out Nils Lofgren’s Try against light, chattering funk, and on the 18-minute 12/8 blues, Blue Sun, she gives an inkling of the stellar career to follow, daringly improvising in dialogue with the tenor and guitar, and outshining both.

The sound quality inevitably varies (with Sonnenberg’s guitar occasionally too dominant), but it’s never less than listenable, and sometimes sensational. The key difference to the lone official album is that these rehearsal tapes better indicate the sheer audacity of the band in concert.